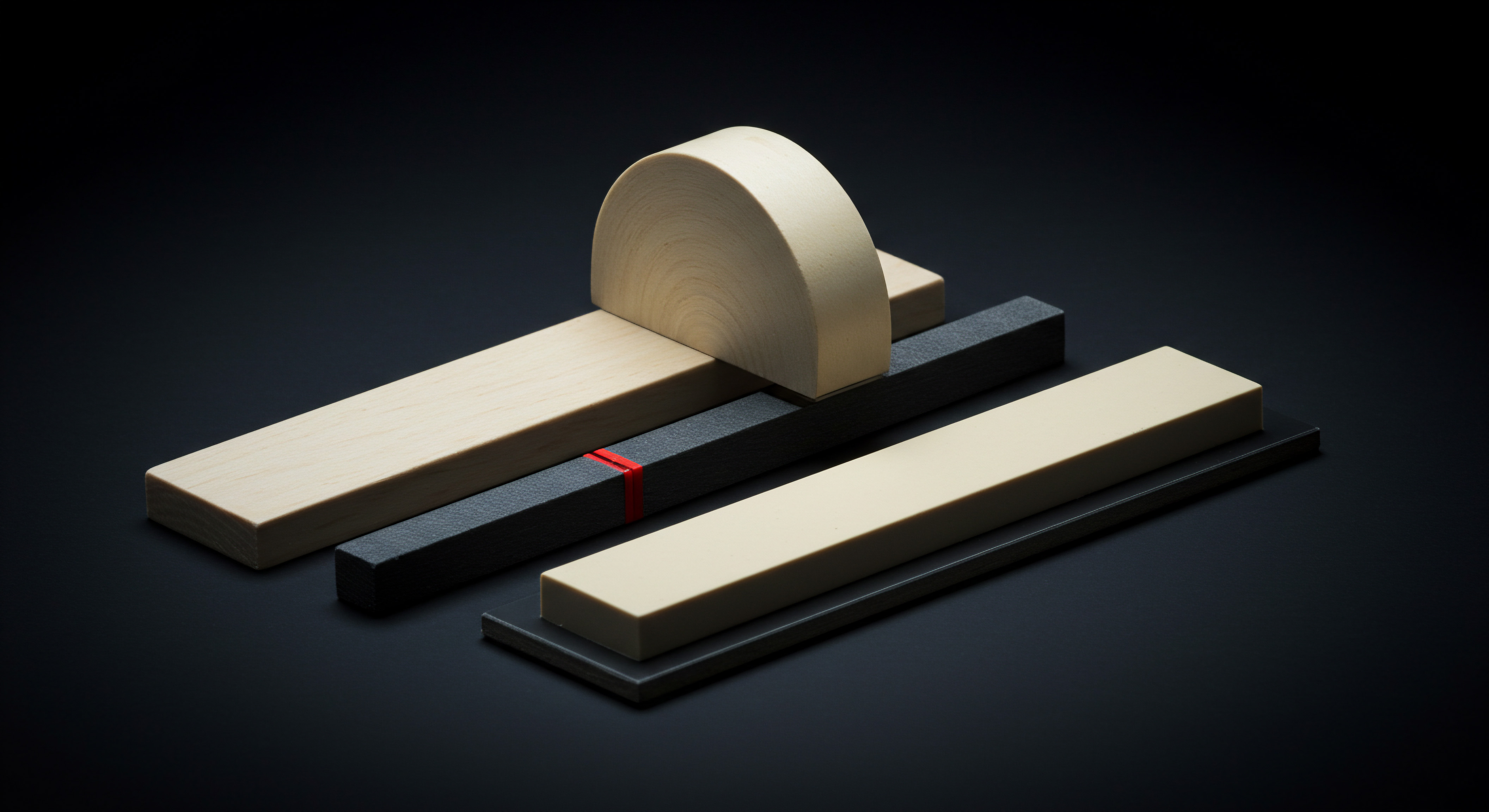

Fundamentals

Thirty percent of small to medium-sized businesses still rely on spreadsheets for critical data analysis. This isn’t just inefficient; it’s a window into a world where automation, poised to reshape the SMB landscape, carries ethical baggage few are unpacking. Automation in SMBs Meaning ● Automation in SMBs is strategically using tech to streamline tasks, innovate, and grow sustainably, not just for efficiency, but for long-term competitive advantage. often conjures images of streamlined workflows and boosted profits, yet lurking beneath the surface are ethical quandaries that demand consideration.

For the Main Street bakery dreaming of online ordering or the local hardware store eyeing inventory management Meaning ● Inventory management, within the context of SMB operations, denotes the systematic approach to sourcing, storing, and selling inventory, both raw materials (if applicable) and finished goods. software, the ethical dimensions of automation might seem abstract, far removed from daily operations. However, ignoring these implications is akin to setting sail without checking the compass; the destination might be reached, but the journey could be fraught with avoidable perils.

The Human Cost of Efficiency

The immediate, and perhaps most visceral, ethical concern revolves around job displacement. Automation, at its core, aims to replace human labor with machines or software to enhance efficiency and reduce costs. For SMBs operating on tight margins, this allure is strong. Consider Sarah, owner of a small accounting firm.

She’s contemplating implementing AI-powered software to automate bookkeeping tasks previously handled by two part-time employees. The software promises to reduce errors and free up Sarah’s time for client consultation, a clear win for efficiency. However, for the two part-time bookkeepers, automation translates into job loss. This scenario isn’t unique; it’s a microcosm of a broader trend across industries.

Automation in customer service Meaning ● Customer service, within the context of SMB growth, involves providing assistance and support to customers before, during, and after a purchase, a vital function for business survival. might mean chatbots replacing human agents. In manufacturing, robots take over assembly line roles. In retail, self-checkout kiosks diminish the need for cashiers. While proponents argue that automation creates new, higher-skilled jobs, the immediate reality for many SMB employees is the threat of redundancy. The ethical question then becomes ● what responsibility does an SMB owner have to their employees when automation renders their roles obsolete?

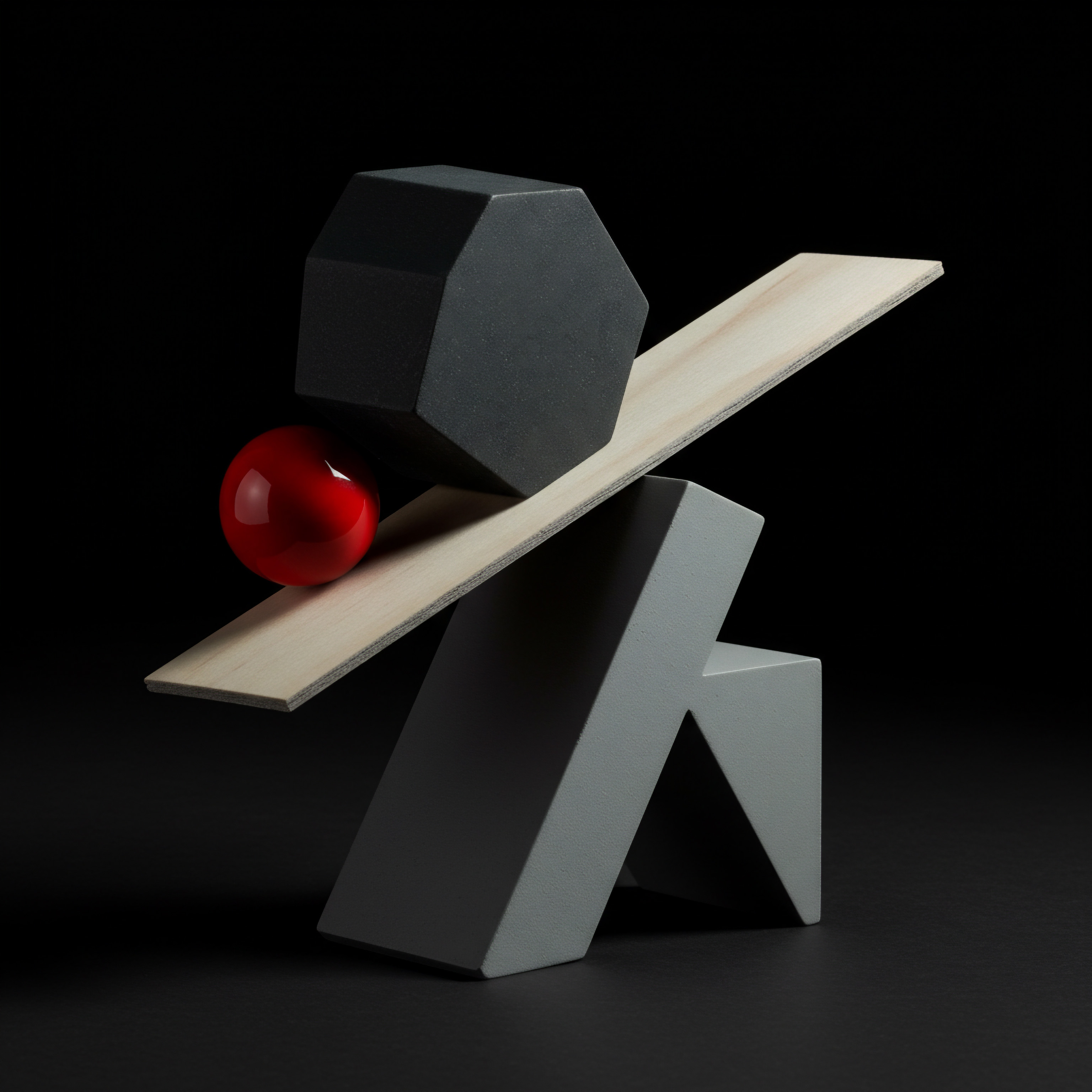

Automation’s promise of efficiency for SMBs casts a long shadow of ethical considerations, demanding a proactive approach to responsible implementation.

Data Privacy in a Streamlined World

Automation thrives on data. From CRM systems tracking customer interactions to marketing automation platforms analyzing consumer behavior, data fuels the engine of efficiency. SMBs, even at a smaller scale, are now custodians of vast amounts of personal information. When automation tools Meaning ● Automation Tools, within the sphere of SMB growth, represent software solutions and digital instruments designed to streamline and automate repetitive business tasks, minimizing manual intervention. process this data, ethical considerations around privacy become paramount.

Imagine a local gym implementing automated membership management software. This system collects member data ● addresses, payment details, workout habits. If this data is not securely stored and handled, it becomes vulnerable to breaches. Beyond security, there’s the question of data usage.

Is the gym transparent with its members about how their data is used? Are members given control over their data? Automation can easily lead to data collection practices that are opaque and potentially exploitative if ethical guidelines are not proactively established. The convenience of automated data processing should not overshadow the fundamental right to privacy.

Algorithmic Bias and Fair Practices

Many automation tools rely on algorithms, sets of rules that guide decision-making. While algorithms offer speed and consistency, they are not inherently neutral. Algorithmic bias, reflecting the biases present in the data used to train them or the assumptions of their creators, can lead to unfair or discriminatory outcomes. Consider an SMB using AI-powered recruitment software to screen job applications.

If the algorithm is trained on historical data that over-represents certain demographics in successful roles, it might inadvertently discriminate against qualified candidates from underrepresented groups. This bias can perpetuate existing inequalities, even if unintentionally. In customer service, chatbots programmed with biased language models could provide less helpful or even discriminatory responses to certain customer demographics. For SMBs striving for fair and equitable practices, understanding and mitigating algorithmic bias Meaning ● Algorithmic bias in SMBs: unfair outcomes from automated systems due to flawed data or design. in their automation tools is an ethical imperative. Blindly trusting algorithms without critical evaluation is a recipe for unintended ethical missteps.

Transparency and Explainability

Automation, particularly when powered by AI, can often feel like a black box. Decisions are made, processes are executed, but the underlying logic remains opaque. This lack of transparency poses ethical challenges, especially when automated systems impact individuals. Suppose a small online lender uses an automated system to assess loan applications.

If an application is rejected, the applicant deserves to understand why. However, if the decision is based on a complex algorithm, providing a clear and understandable explanation becomes difficult. This lack of explainability can erode trust and raise concerns about fairness. For SMBs, embracing automation ethically means prioritizing transparency wherever possible.

Choosing automation tools that offer some degree of explainability, and being prepared to provide clear justifications for automated decisions, is crucial for maintaining ethical standards and building customer trust. Opacity breeds suspicion; transparency fosters confidence.

Maintaining Human Oversight

The allure of full automation ● systems running entirely without human intervention ● is strong. However, ethically sound automation in SMBs necessitates maintaining human oversight. Automation should augment human capabilities, not replace human judgment entirely, especially in areas with ethical implications. Consider a small healthcare clinic automating appointment scheduling and patient communication.

While automation can streamline these processes, human oversight Meaning ● Human Oversight, in the context of SMB automation and growth, constitutes the strategic integration of human judgment and intervention into automated systems and processes. is still vital for handling complex situations, addressing patient concerns, and ensuring compassionate care. In customer service, while chatbots can handle routine inquiries, human agents should be available for complex issues or emotionally charged situations. Automation should free up human employees to focus on tasks requiring empathy, critical thinking, and ethical judgment. Completely relinquishing human control to automated systems, especially in sensitive areas, risks sacrificing ethical considerations for the sake of pure efficiency. Humanity must remain in the loop.

For SMBs venturing into automation, ethical considerations are not roadblocks, but rather guideposts. Addressing these implications proactively, from the outset, allows businesses to harness the benefits of automation responsibly. It’s about building systems that are not only efficient but also fair, transparent, and respectful of human values. This ethical foundation is not just good for society; it’s good for business, fostering trust, loyalty, and a sustainable path to growth in an increasingly automated world.

Intermediate

The global market for robotic process automation (RPA) is projected to reach $13.7 billion by 2028, a figure that underscores the accelerating adoption of automation across businesses of all sizes. For SMBs, this surge in automation presents a complex landscape of ethical considerations that extend beyond the fundamental concerns of job displacement Meaning ● Strategic workforce recalibration in SMBs due to tech, markets, for growth & agility. and data privacy. As SMBs move beyond basic automation tools and explore more sophisticated applications, the ethical implications become more intricate, demanding a more strategic and nuanced approach.

The Shifting Sands of Competitive Advantage

Automation can dramatically alter the competitive landscape for SMBs. Early adopters of automation technologies may gain a significant advantage in terms of efficiency, cost reduction, and service delivery. This creates a potential ethical dilemma ● does the pursuit of competitive advantage Meaning ● SMB Competitive Advantage: Ecosystem-embedded, hyper-personalized value, sustained by strategic automation, ensuring resilience & impact. through automation inadvertently disadvantage businesses that are slower to adopt or lack the resources to invest in these technologies? Consider two competing local retailers, both selling similar products.

Retailer A invests in automated inventory management and online sales platforms, significantly reducing operational costs and expanding market reach. Retailer B, perhaps due to financial constraints or a more traditional business model, lags behind in automation. Retailer A’s increased efficiency allows it to offer lower prices or invest more in marketing, potentially squeezing Retailer B out of the market. While competition is inherent in business, the ethical question arises whether automation-driven competitive advantages create an uneven playing field, particularly for smaller, less technologically advanced SMBs. The drive for innovation should not come at the cost of fair competition and market diversity.

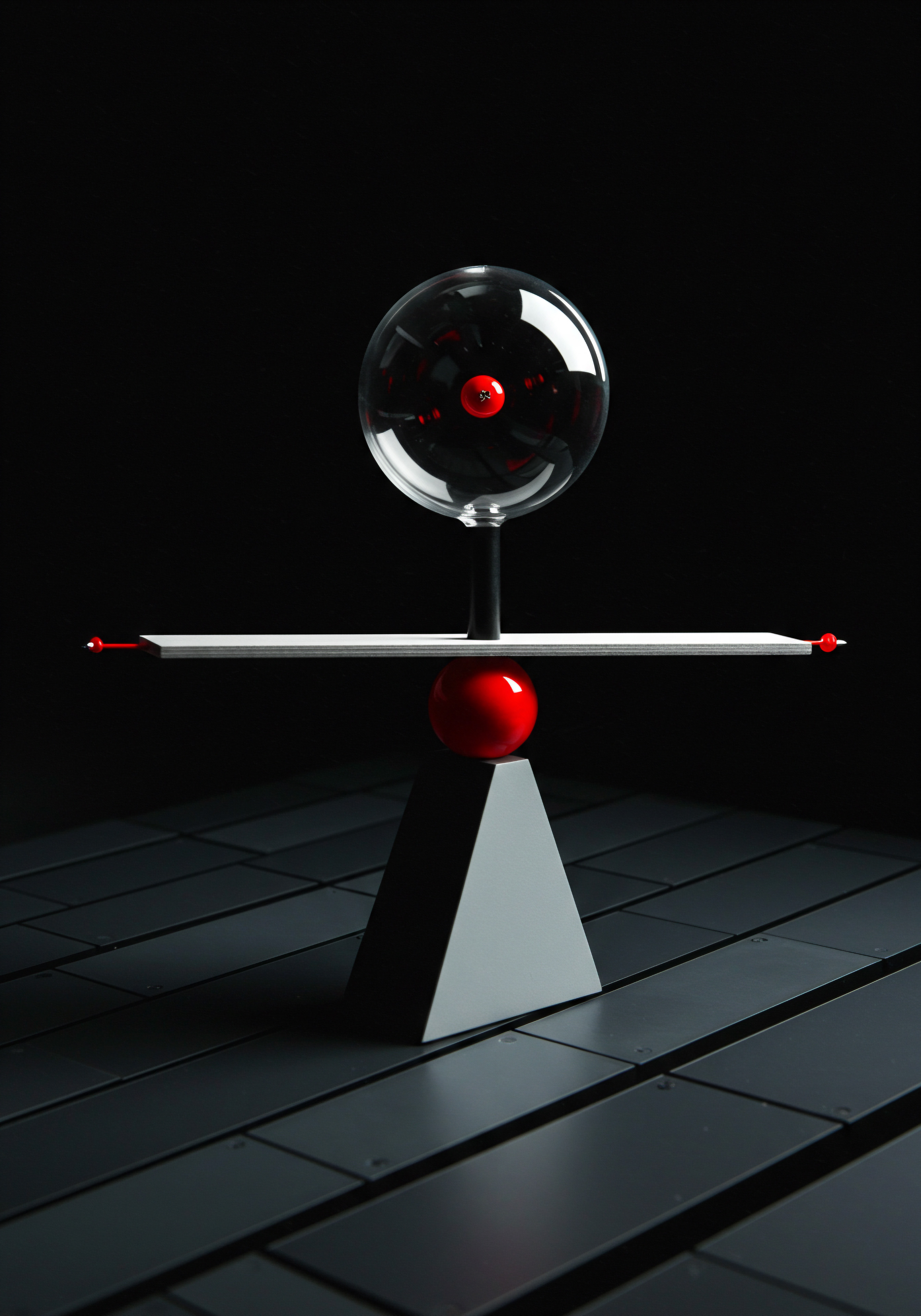

Ethical automation in SMBs necessitates a strategic approach that balances competitive advantage with broader considerations of market fairness and societal impact.

The Ethics of Algorithmic Management

As automation permeates more aspects of SMB operations, algorithmic management Meaning ● Algorithmic management, within the domain of Small and Medium-sized Businesses, refers to the use of algorithms and data analytics to automate and optimize decision-making processes related to workforce management and business operations. ● the use of algorithms to manage and direct employees ● is becoming increasingly prevalent. This can range from automated task assignment and performance monitoring to AI-driven employee scheduling and even automated feedback systems. While algorithmic management promises efficiency gains, it raises significant ethical concerns about employee autonomy, surveillance, and potential bias. Imagine a small logistics company implementing an automated dispatch system that assigns delivery routes and monitors driver performance based on real-time data.

While this system optimizes routes and tracks efficiency, it can also create a sense of constant surveillance for drivers, eroding their autonomy and potentially leading to increased stress. Furthermore, if the algorithms used in these systems are biased or poorly designed, they can lead to unfair performance evaluations and discriminatory outcomes. Ethical algorithmic management requires transparency, employee involvement in system design, and safeguards against bias and undue surveillance. Efficiency gains Meaning ● Efficiency Gains, within the context of Small and Medium-sized Businesses (SMBs), represent the quantifiable improvements in operational productivity and resource utilization realized through strategic initiatives such as automation and process optimization. should not come at the expense of employee well-being and fair treatment.

Supply Chain Automation and Ethical Sourcing

Automation extends beyond internal SMB operations to encompass supply chains. SMBs are increasingly integrating automated systems for procurement, logistics, and supplier management. While supply chain automation Meaning ● Supply Chain Automation for SMBs: Strategically implementing tech to streamline processes, boost efficiency, and enable scalable growth. enhances efficiency and visibility, it also introduces ethical considerations related to sourcing and labor practices within the extended supply network. Consider a small clothing boutique that automates its ordering and inventory replenishment processes.

The automated system might prioritize suppliers offering the lowest prices and fastest delivery times. However, this focus on efficiency could inadvertently lead to sourcing from suppliers with unethical labor practices or unsustainable environmental policies. Ethical supply chain automation requires SMBs to consider the ethical implications of their sourcing decisions, even when driven by automated systems. Integrating ethical and sustainability criteria into automated procurement processes is crucial for ensuring responsible supply chain management. Automation should not blind SMBs to the ethical responsibilities within their broader value chain.

Customer Trust and Automated Interactions

Automation is transforming customer interactions for SMBs. Chatbots, automated email marketing, and AI-powered personalization are becoming commonplace. While these technologies enhance customer service efficiency and personalization, they also raise ethical questions about transparency, authenticity, and the potential for manipulation. Imagine a small e-commerce business using AI-powered chatbots for customer support.

If customers are unaware they are interacting with a bot rather than a human, it can erode trust. Furthermore, automated personalization, while aiming to enhance customer experience, can become manipulative if it crosses the line into intrusive or deceptive marketing tactics. Ethical customer-facing automation requires transparency about automated interactions, respect for customer autonomy, and a focus on genuine value creation rather than manipulation. Building and maintaining customer trust Meaning ● Customer trust for SMBs is the confident reliance customers have in your business to consistently deliver value, act ethically, and responsibly use technology. in an automated world necessitates a commitment to ethical communication and responsible use of customer data.

The Ethical Dimensions of Data Ownership and Access

Automation generates vast amounts of data, raising complex questions about data ownership and access, particularly in the context of SMBs using cloud-based automation platforms. When an SMB relies on a third-party provider for automation services, who owns the data generated by these systems? Does the SMB have full control over its data, or does the platform provider have access and usage rights? These questions have significant ethical implications, particularly concerning data privacy, security, and competitive advantage.

Consider a small restaurant using a cloud-based point-of-sale (POS) system that automates order processing and sales tracking. The POS system collects valuable data about customer preferences, sales trends, and operational efficiency. If the POS provider has broad access rights to this data, it could potentially use it for its own purposes, perhaps even sharing aggregated data with competitors. Ethical automation Meaning ● Ethical Automation for SMBs: Integrating technology responsibly for sustainable growth and equitable outcomes. in SMBs requires careful consideration of data ownership and access agreements with automation platform providers.

SMBs should prioritize data control and ensure they have clear and enforceable rights over the data generated by their automated systems. Data is a valuable asset, and ethical automation requires protecting SMBs’ data rights.

Navigating the ethical landscape of SMB automation Meaning ● SMB Automation: Streamlining SMB operations with technology to boost efficiency, reduce costs, and drive sustainable growth. at the intermediate level requires a proactive and strategic approach. It’s about moving beyond reactive responses to ethical dilemmas and embedding ethical considerations into the very design and implementation of automation strategies. This involves developing ethical frameworks, establishing clear guidelines for data usage and algorithmic management, and fostering a culture of ethical awareness within the SMB. By proactively addressing these intermediate-level ethical challenges, SMBs can harness the transformative power of automation while upholding their ethical responsibilities and building a sustainable and trustworthy business for the future.

Advanced

Academic research indicates that SMEs are increasingly adopting advanced automation Meaning ● Advanced Automation, in the context of Small and Medium-sized Businesses (SMBs), signifies the strategic implementation of sophisticated technologies that move beyond basic task automation to drive significant improvements in business processes, operational efficiency, and scalability. technologies, including artificial intelligence and machine learning, to enhance operational efficiency and strategic decision-making. This progression beyond rudimentary automation scripts into the realm of sophisticated AI-driven systems precipitates a new echelon of ethical complexities for SMBs. These advanced ethical implications transcend immediate concerns, delving into the structural and societal ramifications of widespread SMB automation, demanding a critical and theoretically informed analytical framework.

The Macroeconomic Ethics of Automation and Labor Markets

At a macroeconomic level, the widespread adoption of automation by SMBs contributes to broader shifts in labor markets and income distribution. While individual SMBs may pursue automation for efficiency gains, the aggregate effect across the SMB sector raises ethical questions about societal well-being and economic equity. Consider the scenario where automation leads to significant job displacement across numerous SMBs in a particular sector, such as retail or customer service. While individual businesses may benefit from reduced labor costs, the collective impact could be increased unemployment and social unrest, particularly affecting lower-skilled workers.

This macroeconomic perspective necessitates considering the ethical responsibility of SMBs, as a collective economic force, in mitigating the potential negative societal consequences of automation-driven labor market disruptions. Ethical automation at the advanced level requires SMBs to engage with broader societal implications, potentially through industry collaborations, policy advocacy, and investment in workforce retraining initiatives. The pursuit of micro-level efficiency should not eclipse macro-level ethical obligations to the labor market and social fabric.

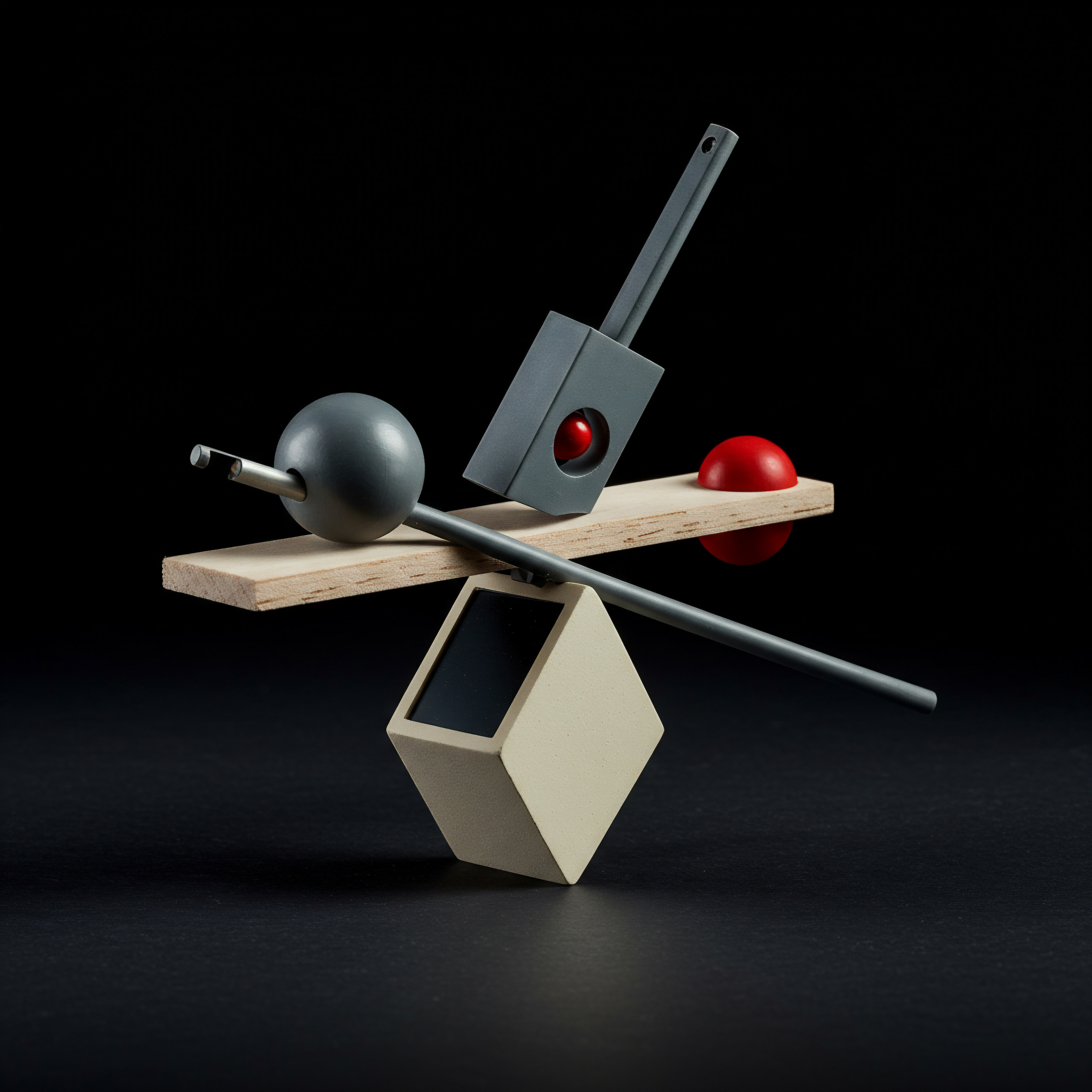

Advanced ethical considerations for SMB automation demand a systemic perspective, encompassing macroeconomic impacts and long-term societal implications beyond individual business gains.

Algorithmic Accountability and the Liability Gap

Advanced automation, particularly AI-driven systems, introduces challenges related to algorithmic accountability Meaning ● Taking responsibility for algorithm-driven outcomes in SMBs, ensuring fairness, transparency, and ethical practices. and the potential for a liability gap. When automated systems make decisions that cause harm or result in unethical outcomes, assigning responsibility becomes complex. Consider an SMB utilizing an AI-powered marketing automation platform that inadvertently disseminates discriminatory or misleading advertising content. Who is accountable for this ethical lapse?

Is it the SMB owner, the platform provider, the algorithm developer, or the data used to train the algorithm? The distributed nature of responsibility in advanced automation systems creates a potential liability gap, where accountability becomes diffused and difficult to enforce. Addressing this ethical challenge requires developing robust frameworks for algorithmic accountability, clarifying liability assignments, and establishing mechanisms for redress when automated systems cause harm. SMBs adopting advanced automation must proactively address the accountability question, ensuring that ethical responsibility is clearly defined and enforceable within their automated operations. Technological advancement should not erode ethical accountability; it necessitates its strengthening.

The Ethics of Autonomous Systems and Human Control

The progression towards increasingly autonomous automation systems in SMBs raises fundamental ethical questions about the appropriate level of human control and intervention. As automation systems become more sophisticated and capable of independent decision-making, the risk of unintended consequences or ethical breaches increases. Consider an SMB deploying autonomous robots in a warehouse environment for inventory management and order fulfillment. While these robots enhance efficiency, they also operate with a degree of autonomy, making decisions based on pre-programmed algorithms and sensor data.

If a robot malfunctions or encounters an unforeseen situation, its autonomous actions could potentially lead to accidents, damage, or ethical dilemmas. Ethical deployment of autonomous systems requires carefully calibrating the level of autonomy with the potential risks and ethical implications. Maintaining human oversight, establishing clear protocols for intervention, and implementing robust safety mechanisms are crucial for ensuring responsible use of autonomous automation in SMBs. Autonomy should be tempered with ethical safeguards and human-in-the-loop oversight.

Data Colonialism and the Ethics of Data Extraction

Advanced automation relies heavily on data, and the increasing reliance on cloud-based platforms and AI-driven analytics raises ethical concerns about data colonialism Meaning ● Data Colonialism, in the context of SMB growth, automation, and implementation, describes the exploitation of SMB-generated data by larger entities, often tech corporations or global conglomerates, for their economic gain. and the potential for data extraction from SMBs by larger technology corporations. When SMBs utilize automation platforms provided by multinational tech companies, they often generate vast amounts of data that is stored and processed by these platforms. This data, while valuable to the SMB, also becomes a valuable asset for the platform provider, potentially used for its own purposes, including training AI models, developing new products, or gaining competitive insights. This dynamic raises ethical questions about data ownership, data sovereignty, and the potential for data extraction from SMBs, particularly in developing economies, by dominant technology players.

Ethical data practices in advanced automation require SMBs to be aware of the data governance policies of their automation platform providers, to negotiate for fair data ownership and access rights, and to consider data localization strategies where appropriate. Data should be treated as a valuable asset, and its ethical governance requires protecting SMBs from potential data colonialism.

The Existential Ethics of Automation and the Future of Work

At the most profound level, advanced automation in SMBs contributes to existential ethical questions about the future of work Meaning ● Evolving work landscape for SMBs, driven by tech, demanding strategic adaptation for growth. and the evolving relationship between humans and technology. As automation capabilities expand, the nature of work itself is transforming, potentially leading to a future where human labor is increasingly displaced by machines across a wide range of sectors, including those traditionally dominated by SMBs. This raises fundamental ethical questions about the purpose of work, the meaning of human contribution, and the societal implications of widespread technological unemployment. While these questions are broad and complex, SMBs, as key actors in the economy, have a role to play in shaping a future of work that is ethically sound and socially beneficial.

This may involve exploring new models of work, supporting universal basic income initiatives, investing in education and retraining for future-oriented skills, and advocating for policies that promote a just transition in the face of automation-driven labor market changes. Ethical leadership in the age of advanced automation requires SMBs to engage with these existential questions and to contribute to building a future where technology serves humanity, rather than the other way around. Automation’s ultimate ethical test lies in its impact on the human condition and the future of work itself.

Addressing the advanced ethical implications of SMB automation necessitates a paradigm shift from reactive risk management to proactive ethical innovation. It requires SMBs to adopt a more critical, systemic, and future-oriented perspective, engaging with ethical considerations not just as compliance obligations, but as opportunities for value creation and societal contribution. This involves fostering ethical leadership, promoting interdisciplinary collaboration, investing in ethical AI research and development, and actively participating in shaping the ethical and policy landscape of automation. By embracing this advanced ethical agenda, SMBs can not only navigate the complexities of automation responsibly but also contribute to building a more just, equitable, and human-centered future in the age of intelligent machines.

References

- Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. “The China Syndrome ● Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States.” American Economic Review, vol. 103, no. 3, 2013, pp. 2121-68.

- Brynjolfsson, Erik, and Andrew McAfee. Race Against the Machine ● How the Digital Revolution Is Accelerating Innovation, Driving Productivity, and Irreversibly Transforming Employment and the Economy. Digital Frontier Press, 2011.

- Davenport, Thomas H., and Julia Kirby. “Just How Smart Are Smart Machines?” Harvard Business Review, vol. 93, no. 3, 2015, pp. 54-65.

- Manyika, James, et al. A Future That Works ● Automation, Employment, and Productivity. McKinsey Global Institute, 2017.

Reflection

Perhaps the most uncomfortable truth about SMB automation isn’t about job losses or data breaches, but about the subtle erosion of human distinctiveness. As we automate tasks once considered uniquely human ● creativity, empathy, even ethical judgment ● we risk diminishing the very qualities that define us. The relentless pursuit of efficiency, while understandable in the competitive SMB landscape, should not come at the cost of our own humanity.

Automation, in its most profound ethical dimension, compels us to reconsider what it means to be human in a world increasingly populated by intelligent machines. This introspection, rather than mere risk mitigation, should guide the ethical trajectory of SMB automation.

SMB automation ethics ● balancing efficiency with fairness, transparency, and human values in an increasingly automated business world.

Explore

What Are Key Ethical Automation Challenges for SMBs?

How Can SMBs Ensure Ethical Algorithmic Accountability?

To What Extent Does Automation Reshape SMB Labor Practices Ethically?