Fundamentals

Consider the local bakery, a small business often seen as immune to grand economic shifts. Yet, even here, the hum of a new automated mixer replaces the rhythmic slap of dough against the counter, a subtle shift echoing a larger transformation. This change, seemingly minor, is a microcosm of automation’s pervasive reach, and the business data Meaning ● Business data, for SMBs, is the strategic asset driving informed decisions, growth, and competitive advantage in the digital age. reflecting its societal impact Meaning ● Societal Impact for SMBs: The total effect a business has on society and the environment, encompassing ethical practices, community contributions, and sustainability. is far from subtle when aggregated across sectors and time.

Efficiency Gains Versus Workforce Shifts

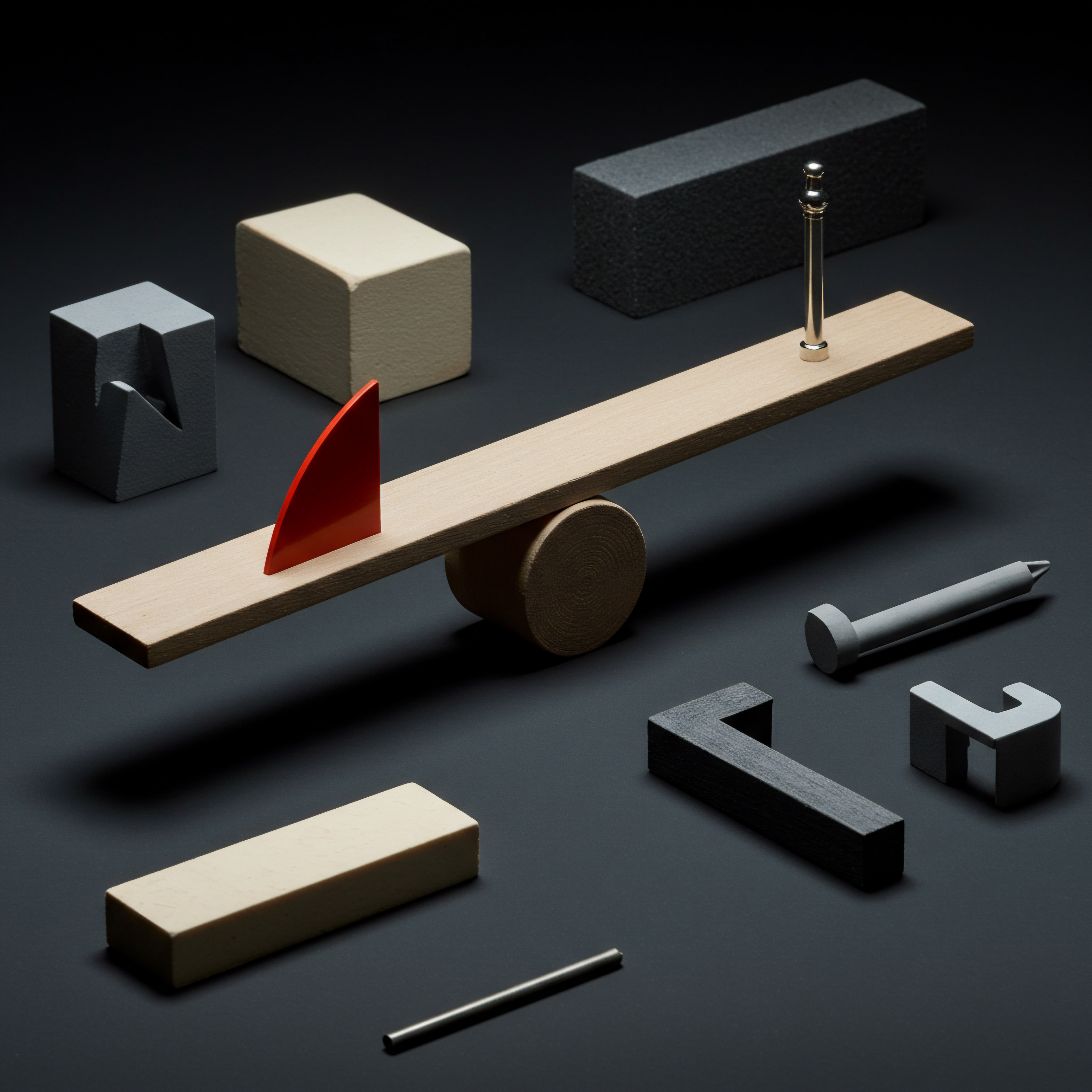

For the small business owner, the allure of automation often begins with a simple equation ● reduced costs equal increased profits. Initial data points frequently highlight operational efficiency. Consider metrics like Production Output Per Labor Hour. A bakery, after automating its mixing process, might see a 30% increase in loaves produced per hour of staff time.

This is concrete, tangible data. Similarly, Error Rates often plummet. Automated systems, programmed for precision, consistently outperform human labor in repetitive tasks, reducing waste and improving product consistency. Tracking Customer Satisfaction Scores pre- and post-automation can reveal improvements linked to this consistency and potentially faster service. These are the immediate, appealing data points that drive initial adoption, particularly for SMBs operating on tight margins.

Automation initially presents itself as a straightforward efficiency upgrade, but its societal ripples are far more complex than simple cost savings.

However, this focus on efficiency overlooks a critical part of the equation ● the workforce. The bakery example, while showing output gains, also implies a potential reduction in labor needs. Payroll Data becomes a crucial indicator here. While automation might not immediately lead to mass layoffs in a small bakery, it could mean fewer new hires are needed as the business grows, or a shift in roles towards managing and maintaining automated systems rather than hands-on production.

At a broader societal level, tracking Employment Rates by Sector, particularly in industries undergoing rapid automation, provides a clearer picture. A decline in manufacturing jobs, coupled with a rise in technology-related service roles, signals a significant societal shift driven, in part, by automation. Wage Stagnation or decline in certain sectors, despite overall economic growth, can also be a telling data point, suggesting that the benefits of automation are not evenly distributed across the workforce.

Skills Evolution and the Education Imperative

Automation doesn’t simply eliminate jobs; it fundamentally alters the skills landscape. The demand for manual, repetitive tasks decreases, while the need for technical skills ● programming, data analysis, system maintenance ● increases. Job Posting Data reflects this shift. Analyzing the skills listed in job descriptions over time reveals a growing emphasis on digital literacy and technical proficiency, even for roles traditionally considered non-technical.

For SMBs, this means a changing hiring landscape and a need to invest in upskilling existing employees. Training Expenditure Data within SMBs can indicate their responsiveness to this skills evolution. Are small businesses actively investing in training programs to equip their workforce for an automated future, or are they lagging behind, potentially exacerbating societal inequalities?

Furthermore, the societal impact extends to the education system. Enrollment Rates in STEM Fields (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) at colleges and vocational schools are crucial indicators. An increase in STEM enrollment suggests a societal adaptation to the changing demands of the automated economy. However, access to quality STEM education is not uniform.

Data on Educational Attainment by Socioeconomic Background can reveal disparities, indicating whether automation is creating a skills divide, where those from disadvantaged backgrounds are less equipped to participate in the new economy. This data highlights the societal responsibility to ensure equitable access to education and training that aligns with the skills demanded by an automated world.

Consumer Behavior and Market Dynamics

Automation also reshapes consumer behavior and market dynamics. E-Commerce Sales Data provides a clear example. Automated warehouses and logistics systems have fueled the growth of online retail, offering consumers unprecedented convenience and choice.

This shift impacts brick-and-mortar SMBs, requiring them to adapt to changing consumer expectations. Foot Traffic Data in retail areas can indicate the extent of this impact, with declines potentially signaling a need for SMBs to embrace online channels or offer unique in-person experiences that automation cannot replicate.

Consumer preference for convenience, enabled by automation, reshapes markets and forces SMBs to adapt or risk obsolescence.

Moreover, automation influences product pricing and availability. Increased efficiency can lead to lower production costs, potentially translating to lower prices for consumers. Inflation Data, particularly for goods and services heavily impacted by automation, can reflect this trend. However, this price deflation can also squeeze profit margins for SMBs, particularly those competing with larger, more automated corporations.

Market Share Data, showing the distribution of sales across different business sizes, can reveal whether automation is contributing to market consolidation, favoring large corporations at the expense of SMBs. Understanding these market dynamics is crucial for SMBs to strategize and for policymakers to ensure a level playing field in an increasingly automated economy.

Initial Steps for SMBs ● Data-Driven Adaptation

For SMBs navigating this evolving landscape, the first step is often simply acknowledging the shift and beginning to track relevant data. This doesn’t require complex systems initially. Simple spreadsheets tracking Sales Data by Channel (online vs. in-store), Customer Feedback Related to Service Speed or Product Quality, and Basic Employee Time Tracking can provide valuable insights.

Analyzing this data, even in a rudimentary way, allows SMB owners to identify areas where automation might offer tangible benefits and to understand how their business is being impacted by broader automation trends. For example, a restaurant owner might notice increasing online order volume and customer feedback praising online ordering convenience. This data suggests investing in a more robust online ordering system, perhaps with automated order processing, could be a worthwhile step.

Furthermore, SMBs can leverage publicly available data to understand broader societal trends. Government reports on Employment Statistics, industry publications analyzing Automation Adoption Rates in Specific Sectors, and even local demographic data can provide context and inform strategic decisions. For instance, a small retail store owner might consult local demographic data to understand the age distribution of their customer base.

If the data shows a growing younger demographic, who are typically more comfortable with online shopping and automated services, this reinforces the need to consider an online presence or automated self-checkout options in-store. The key for SMBs is to move from anecdotal observations to data-informed decision-making, even on a small scale, to navigate the societal impacts of automation effectively.

Intermediate

Beyond the initial efficiency gains, automation’s societal impact, as revealed through business data, presents a more intricate picture. Consider the rise of algorithmic management, where software dictates work schedules and performance evaluations. While optimizing productivity, this data-driven approach raises questions about worker autonomy and the qualitative aspects of labor, aspects often overlooked in purely quantitative analyses. The data points we examine at this stage move beyond simple input-output ratios, probing deeper into the structural and human dimensions of automation’s influence.

Productivity Paradox Revisited ● Beyond Simple Output Metrics

The initial promise of automation centers on boosting productivity, measured by metrics like Total Factor Productivity (TFP). However, economic history reveals a “productivity paradox,” where significant technological investments don’t always translate into immediate or proportional productivity gains. Analyzing Sector-Specific Productivity Growth alongside Automation Investment Data can reveal whether this paradox persists in the current wave of automation. For SMBs, this means that simply adopting automation technology doesn’t guarantee immediate profitability.

Return on Investment (ROI) Timelines for automation projects become critical data points. Longer-than-expected ROI periods can strain SMB finances, particularly if initial productivity gains are offset by implementation costs, learning curves, or unforeseen integration challenges.

Productivity gains from automation are not always immediate or linear; SMBs must consider the full ROI timeline and potential paradoxes.

Furthermore, focusing solely on output metrics overlooks the qualitative aspects of productivity. Employee Engagement Scores and Employee Turnover Rates can be leading indicators of the human impact of automation. If automation leads to deskilling or a sense of diminished purpose among employees, productivity gains might be offset by decreased morale and higher turnover costs. Absenteeism Rates and Employee Health Insurance Claims can also indirectly reflect the impact of automation on workforce well-being.

For SMBs, particularly those in service industries where human interaction remains crucial, maintaining a motivated and engaged workforce is paramount, even as they integrate automation into their operations. Data analysis Meaning ● Data analysis, in the context of Small and Medium-sized Businesses (SMBs), represents a critical business process of inspecting, cleansing, transforming, and modeling data with the goal of discovering useful information, informing conclusions, and supporting strategic decision-making. must therefore extend beyond simple output figures to encompass the broader human capital Meaning ● Human Capital is the strategic asset of employee skills and knowledge, crucial for SMB growth, especially when augmented by automation. implications.

Data Bias and Algorithmic Inequity

Automation increasingly relies on algorithms trained on vast datasets. However, if these datasets reflect existing societal biases, the automated systems can perpetuate and even amplify these inequities. Audit Logs of Automated Decision-Making Systems, while often proprietary, are crucial data sources for identifying potential bias. In areas like loan applications or hiring processes, automated systems might inadvertently discriminate against certain demographic groups if the training data reflects historical biases.

Data on Loan Approval Rates by Demographic Group or Hiring Rates by Demographic Group, when analyzed in conjunction with the use of automated decision-making tools, can reveal potential algorithmic bias. For SMBs using automated tools for customer service, marketing, or HR, understanding and mitigating data bias is not only ethically responsible but also crucial for maintaining a fair and inclusive business environment.

The societal impact of algorithmic bias Meaning ● Algorithmic bias in SMBs: unfair outcomes from automated systems due to flawed data or design. extends beyond individual businesses. Data on Access to Opportunities and Resources by Demographic Group, across sectors and regions, can reveal systemic inequities potentially exacerbated by automation. For example, if automated job recruitment platforms disproportionately favor certain demographics, this can reinforce existing labor market inequalities.

Public Sentiment Analysis Data, gathered from social media and online forums, can also reflect public awareness and concern about algorithmic bias. Monitoring these broader societal data points helps SMBs understand the ethical and reputational risks associated with automation and encourages a more responsible approach to technology adoption.

Supply Chain Resilience and Geopolitical Considerations

Automation reshapes global supply chains, often increasing efficiency and reducing costs but also potentially increasing vulnerability to disruptions. Supply Chain Mapping Data, visualizing the interconnectedness of suppliers and distributors, reveals the complexity and potential fragility of modern supply chains. Automation, by concentrating production in fewer, more efficient facilities, can create single points of failure. Data on Supply Chain Disruptions, such as factory shutdowns due to pandemics or geopolitical events, highlights the risks associated with overly optimized, globally dispersed supply chains.

For SMBs reliant on these global supply chains, resilience becomes a critical strategic consideration. Inventory Management Data, showing stock levels and lead times, and Supplier Diversification Metrics, tracking the number and geographic distribution of suppliers, are crucial for assessing and mitigating supply chain risks in an automated world.

Furthermore, automation intersects with geopolitical considerations. The race to develop and deploy advanced automation Meaning ● Advanced Automation, in the context of Small and Medium-sized Businesses (SMBs), signifies the strategic implementation of sophisticated technologies that move beyond basic task automation to drive significant improvements in business processes, operational efficiency, and scalability. technologies is becoming a key area of international competition. Data on R&D Spending in Automation Technologies by Country and Patent Filings in Automation Technologies by Country reflect this global race. For SMBs, this geopolitical dimension translates into potential shifts in competitive landscapes, trade policies, and access to technology.

Trade Balance Data in Automation-Related Industries and Foreign Direct Investment Data in Automation Sectors can provide insights into these global shifts. Understanding these broader geopolitical trends helps SMBs anticipate future challenges and opportunities in an increasingly automated and interconnected world.

Advanced SMB Strategies ● Data-Driven Ecosystem Participation

For SMBs to thrive in this intermediate stage of automation’s societal impact, a more proactive, data-driven approach is needed. This involves not just passively tracking internal data but actively participating in data ecosystems and industry collaborations. Industry Benchmark Data, comparing SMB performance metrics against industry averages, provides valuable context and identifies areas for improvement.

Data Sharing Initiatives within Industry Associations can enable SMBs to collectively analyze trends and develop shared solutions to automation-related challenges. For example, a group of small retailers might pool anonymized sales data to identify emerging consumer preferences and optimize inventory management collectively.

SMBs must move beyond internal data tracking to participate in data ecosystems and industry collaborations for collective intelligence and resilience.

Moreover, SMBs can leverage data to advocate for policies that support a more equitable and sustainable automation transition. Data on the Impact of Automation on Local Communities, such as job displacement Meaning ● Strategic workforce recalibration in SMBs due to tech, markets, for growth & agility. rates or changes in local economic indicators, can be powerful tools for influencing policy decisions. Participation in Industry Advocacy Groups and Engagement with Policymakers, informed by data analysis, allows SMBs to shape the broader societal narrative around automation and ensure their voices are heard in policy debates. This proactive, data-driven engagement is essential for SMBs to navigate the intermediate complexities of automation’s societal impact and contribute to a more inclusive and prosperous future.

Advanced

The advanced stage of automation’s societal impact, viewed through the lens of business data, reveals a landscape of systemic transformation, demanding a recalibration of fundamental business paradigms and societal structures. We move beyond incremental efficiency improvements and localized disruptions to confront the potential for widespread economic restructuring and profound shifts in the social contract. The data points at this level are not merely metrics of operational performance but indicators of systemic resilience, societal equity, and the very nature of work in an increasingly autonomous world.

Consider the burgeoning gig economy, a data-driven construct enabled by automation, blurring traditional employment boundaries and raising complex questions about labor rights, social safety nets, and the future of work Meaning ● Evolving work landscape for SMBs, driven by tech, demanding strategic adaptation for growth. itself. This is not simply about automating tasks; it is about automating systems and, consequently, reshaping society.

Systemic Risk and Economic Reconfiguration

Automation, at its advanced stages, introduces systemic risks that traditional business risk models often fail to capture. Inter-Industry Dependency Data, mapping the complex web of relationships between sectors, reveals vulnerabilities to cascading failures. Automation in one sector, while boosting its efficiency, can create bottlenecks or dependencies in others. Stress Test Data for Critical Infrastructure, including energy grids, transportation networks, and communication systems, becomes paramount.

These systems, increasingly reliant on automation, are susceptible to cyberattacks, algorithmic errors, or unforeseen systemic shocks. Financial Contagion Risk Data, analyzing the interconnectedness of financial institutions and markets, highlights the potential for automation-driven disruptions to ripple through the global economy. For corporations and policymakers alike, understanding and mitigating these systemic risks is no longer a peripheral concern but a core strategic imperative.

Advanced automation necessitates a shift from localized risk management to systemic risk mitigation, demanding inter-industry collaboration and robust infrastructure resilience.

Furthermore, advanced automation drives a fundamental reconfiguration of economic structures. Data on the Concentration of Economic Power, measured by metrics like the Gini coefficient of corporate revenue or the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) in key sectors, can reveal whether automation is exacerbating market concentration and creating winner-take-all dynamics. Labor Share of Income Data, tracking the proportion of national income going to wages versus capital, provides insights into the distributional effects of automation. A declining labor share, coupled with rising capital returns, suggests a potential widening of income inequality.

Social Mobility Data, analyzing intergenerational income mobility, can indicate whether automation is creating structural barriers to upward mobility for certain segments of society. These macroeconomic data points are crucial for understanding the long-term societal consequences of advanced automation and for formulating policies that promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth.

The Algorithmic State and Data Governance

Advanced automation increasingly intersects with the role of the state, raising complex questions about data governance, algorithmic accountability, and the balance between efficiency and societal values. Data on Government Adoption of Automated Systems, in areas like public services, law enforcement, and social welfare, reveals the growing influence of algorithms in governance. Transparency Metrics for Government Algorithms, assessing the openness and explainability of these systems, are crucial for ensuring public trust and accountability.

Citizen Data Privacy and Security Metrics, tracking data breaches and surveillance activities, highlight the potential risks associated with the increasing collection and processing of personal data by both government and private entities. For SMBs, navigating this evolving landscape of data governance Meaning ● Data Governance for SMBs strategically manages data to achieve business goals, foster innovation, and gain a competitive edge. requires a proactive approach to data ethics, compliance, and cybersecurity.

The societal impact of the “algorithmic state” extends to the very nature of democratic governance. Data on Public Discourse and Opinion Formation Online, analyzing social media trends and information flows, reveals the potential for automation to influence public opinion and political processes. Misinformation and Disinformation Spread Metrics, tracking the prevalence and impact of false or misleading information, highlight the risks to democratic discourse in an age of automated content generation and dissemination.

Civic Engagement Data, measuring voter turnout and participation in democratic processes, can indicate whether automation is contributing to political polarization or disengagement. Addressing these challenges requires a multi-faceted approach, involving media literacy initiatives, algorithmic transparency regulations, and robust public discourse platforms.

The Future of Work and Human Capital Redefinition

Advanced automation necessitates a fundamental redefinition of work and human capital. Data on the Skills Gap, comparing the skills demanded by the automated economy with the skills possessed by the workforce, reveals the scale of the reskilling and upskilling challenge. Lifelong Learning Participation Rates, tracking adult education and training activities, indicate societal responsiveness to this challenge. Data on the Gig Economy and Alternative Work Arrangements, analyzing the growth and characteristics of non-traditional employment, highlights the shifting nature of work relationships.

Universal Basic Income (UBI) Pilot Program Data, assessing the economic and social impacts of providing a basic income guarantee, explores potential alternative social safety nets in an automated future. For SMBs, adapting to this future of work requires embracing flexible work models, investing in continuous employee development, and fostering a culture of adaptability and innovation.

The societal impact of this work transformation extends to the very definition of human value and purpose. Data on Mental Health and Well-Being, tracking rates of anxiety, depression, and social isolation, can reflect the psychological impact of automation-driven job displacement and economic insecurity. Social Capital Metrics, measuring community cohesion and social connectedness, indicate the broader societal consequences of changing work patterns and social structures.

Data on Creative Industries and the Passion Economy, analyzing the growth of sectors driven by human creativity and intrinsic motivation, suggests potential new avenues for human fulfillment in an automated world. Navigating this profound societal transformation requires a holistic approach, encompassing economic policies, educational reforms, and a renewed focus on human flourishing beyond traditional notions of work and productivity.

Strategic Corporate and Societal Co-Evolution

In this advanced stage, the relationship between corporations and society must evolve towards a model of co-evolution, where business strategy is intrinsically linked to societal well-being. ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) Performance Data, tracking corporate performance across these dimensions, becomes a critical indicator of corporate responsibility and long-term sustainability. Stakeholder Capitalism Metrics, assessing corporate value creation for all stakeholders, not just shareholders, reflect a shift towards a more inclusive business model.

Data on Corporate Social Innovation and Impact Investing, analyzing investments in solutions to societal challenges, highlights the potential for business to be a force for positive social change. For SMBs, embracing these principles of corporate social responsibility is not just ethically sound but also strategically advantageous in attracting talent, building brand loyalty, and ensuring long-term resilience in an increasingly interconnected and conscious world.

Advanced automation demands a co-evolution of corporate strategy and societal well-being, where ESG principles and stakeholder capitalism become integral to business models.

Furthermore, societal resilience in the face of advanced automation requires proactive policy interventions and collaborative governance models. Data on the Effectiveness of Retraining Programs and Social Safety Nets, assessing their impact on mitigating job displacement and income inequality, informs evidence-based policymaking. Public-Private Partnerships in Automation Research and Development, fostering collaboration between government, industry, and academia, accelerate innovation while ensuring alignment with societal goals.

Global Governance Frameworks for Automation Ethics and Regulation, promoting international cooperation and shared standards, are essential for navigating the transnational challenges of advanced automation. This collaborative, data-informed approach to governance is crucial for harnessing the benefits of automation while mitigating its risks and ensuring a future where technology serves humanity, not the other way around.

References

- Acemoglu, Daron, and Pascual Restrepo. “Automation and New Tasks ● How Technology Displaces and Reinstates Labor.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 33, no. 2, 2019, pp. 3-30.

- Brynjolfsson, Erik, and Andrew McAfee. The Second Machine Age ● Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. W. W. Norton & Company, 2014.

- Manyika, James, et al. A Future That Works ● Automation, Employment, and Productivity. McKinsey Global Institute, 2017.

- Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Belknap Press, 2014.

Reflection

Perhaps the most telling business data point indicating automation’s societal impact is not found in spreadsheets or algorithms, but in the quiet anxieties of the entrepreneur contemplating their legacy. Will their automated business contribute to a more equitable and prosperous society, or will it inadvertently accelerate the very trends that erode the human fabric of their communities? This unquantifiable, deeply human concern, reflected in countless conversations in small business forums and whispered in boardroom meetings, might be the most critical data of all, urging a more conscious and human-centered approach to automation’s relentless advance.

Business data reveals automation’s societal impact through efficiency gains, workforce shifts, skills evolution, market dynamics, systemic risks, algorithmic biases, and the need for co-evolution between business and society.

Explore

What Data Reveals Automation’s Impact on SMB Growth?

How Do Automation Metrics Indicate Workforce Skill Shifts?

Why Is Algorithmic Bias Data Crucial for Societal Equity?