Fundamentals

Ninety percent of businesses globally are categorized as small to medium-sized businesses (SMBs), yet their adoption of automation technologies lags significantly behind larger corporations, creating a learning paradox. SMBs, often operating with limited resources and personnel, stand to gain considerably from automation, but the very constraints that necessitate automation can also impede their capacity to learn and adapt alongside these technological shifts. This presents a critical question ● How does the drive to automate processes within SMBs shape their ability to learn, evolve, and remain competitive in an ever-changing market landscape?

The Dichotomy of Automation and Learning

Automation, at its core, is about streamlining operations, reducing manual tasks, and enhancing efficiency. For SMBs, this can translate to significant benefits ● lower operational costs, improved accuracy, and the ability to scale without proportionally increasing headcount. However, organizational learning Meaning ● Organizational Learning: SMB's continuous improvement through experience, driving growth and adaptability. is a different beast. It involves the processes through which companies acquire, retain, and transfer knowledge, adapting their behavior in response to new information and experiences.

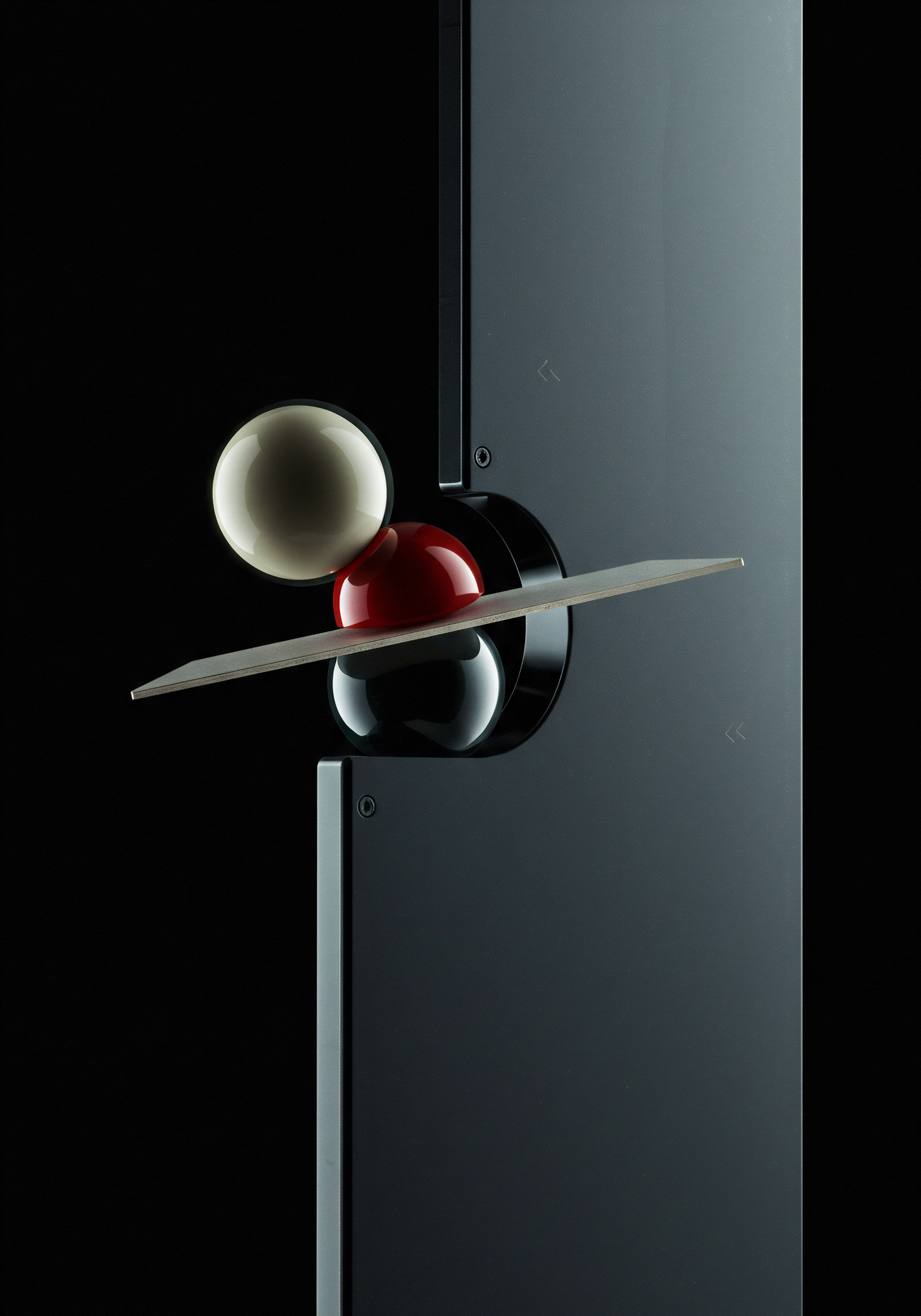

The relationship between these two forces ● automation and organizational learning ● is not always straightforward. It’s a complex interplay where the pursuit of efficiency through automation can sometimes inadvertently undermine the very learning processes that are essential for long-term organizational health and growth.

Automation in SMBs presents a double-edged sword, promising efficiency gains Meaning ● Efficiency Gains, within the context of Small and Medium-sized Businesses (SMBs), represent the quantifiable improvements in operational productivity and resource utilization realized through strategic initiatives such as automation and process optimization. while potentially complicating the very processes of learning and adaptation crucial for sustained success.

Initial Impacts ● Efficiency Versus Exploration

When SMBs first implement automation, the immediate impact is often felt in operational efficiency. Tasks that were once time-consuming and prone to error, such as data entry, invoice processing, or basic customer service inquiries, can be handled swiftly and accurately by automated systems. This initial phase can be exhilarating for an SMB. Suddenly, employees have more time, processes run smoother, and there’s a tangible sense of progress.

However, this focus on efficiency can overshadow a critical aspect of organizational learning ● exploration. Learning isn’t just about doing things faster; it’s also about discovering new approaches, experimenting with different strategies, and adapting to unforeseen challenges. If automation is implemented solely with efficiency in mind, it can create an environment where exploration and experimentation are inadvertently stifled.

The Human Element in Automated Environments

Consider a small retail business adopting a point-of-sale (POS) system with automated inventory management. Previously, employees manually tracked inventory, gaining firsthand insights into product movement, customer preferences, and seasonal trends. With automation, this process becomes streamlined. The system automatically updates inventory levels, generates reports, and even reorders stock based on pre-set algorithms.

While this undoubtedly improves efficiency and reduces stockouts, it can also diminish the direct interaction employees have with inventory data. The tacit knowledge Meaning ● Tacit Knowledge, in the realm of SMBs, signifies the unwritten, unspoken, and often unconscious knowledge gained from experience and ingrained within the organization's people. gained from physically handling inventory, observing customer buying patterns, and troubleshooting discrepancies is lost. Employees become reliant on the system’s outputs, potentially losing the ability to critically assess the data or identify anomalies that the system might miss. This shift highlights a key challenge ● how to maintain the human element of learning within increasingly automated environments.

Learning Through Automation Implementation

Interestingly, the very process of implementing automation can itself be a significant learning opportunity for SMBs. Choosing the right automation tools, integrating them with existing systems, and training employees to use them effectively requires SMBs to engage in problem-solving, adaptation, and knowledge acquisition. This implementation phase can force SMBs to examine their existing processes, identify bottlenecks, and rethink workflows.

For instance, a small manufacturing company deciding to automate a portion of its production line might need to learn about different types of automation technologies, assess their compatibility with existing equipment, and develop new skill sets within their workforce. This learning, however, is often project-specific and may not translate into broader organizational learning capabilities if not consciously managed and disseminated across the company.

Table ● Initial Impacts of Automation on Organizational Learning in SMBs

Initial Impact Category

Description

Potential Benefit

Potential Challenge to Organizational Learning

Efficiency Gains

Streamlining of routine tasks, faster processing times, reduced errors.

Increased productivity, lower operational costs.

Overemphasis on efficiency may overshadow exploration and experimentation.

Reduced Manual Tasks

Automation of repetitive and labor-intensive processes.

Frees up employee time for higher-value activities.

Loss of tacit knowledge gained from manual processes; deskilling potential.

Data-Driven Insights

Automated systems generate data and reports on key performance indicators.

Improved decision-making based on real-time data.

Over-reliance on system-generated data; potential for “automation bias” and reduced critical assessment.

Implementation Learning

The process of selecting, integrating, and deploying automation technologies.

Forces process review, problem-solving, and skill development.

Learning may be project-specific and not systematically captured or shared across the organization.

Navigating the Fundamental Shift

For SMBs to effectively navigate the impact of automation on organizational learning, a fundamental shift in mindset is required. Automation should not be viewed solely as a tool for cost reduction or efficiency gains. Instead, it should be considered a strategic enabler of organizational learning. This means proactively designing automation implementations to foster learning, rather than inadvertently hindering it.

It involves consciously preserving the human element in automated processes, creating opportunities for employees to learn from automation data, and ensuring that the learning gained during automation implementation is captured and disseminated throughout the organization. The challenge for SMBs is to harness the power of automation while simultaneously nurturing a culture of continuous learning and adaptation. This is not a simple balancing act; it requires a deliberate and strategic approach to integrating automation into the very fabric of the SMB’s operational and learning processes.

SMBs must strategically approach automation not just for efficiency, but as a catalyst for enhanced organizational learning and adaptability.

Intermediate

The narrative surrounding automation in small to medium-sized businesses often centers on the promise of enhanced productivity and streamlined operations. However, a more critical examination reveals a complex interplay between automation and organizational learning, particularly when considering the diverse learning styles and resource constraints inherent in SMBs. While large corporations may possess dedicated learning and development departments to manage technological transitions, SMBs frequently rely on informal learning processes and the inherent adaptability of their smaller teams. Therefore, the introduction of automation technologies into this environment can have profound, and sometimes unanticipated, consequences for how these organizations learn and evolve.

Beyond Efficiency ● Automation’s Influence on Learning Types

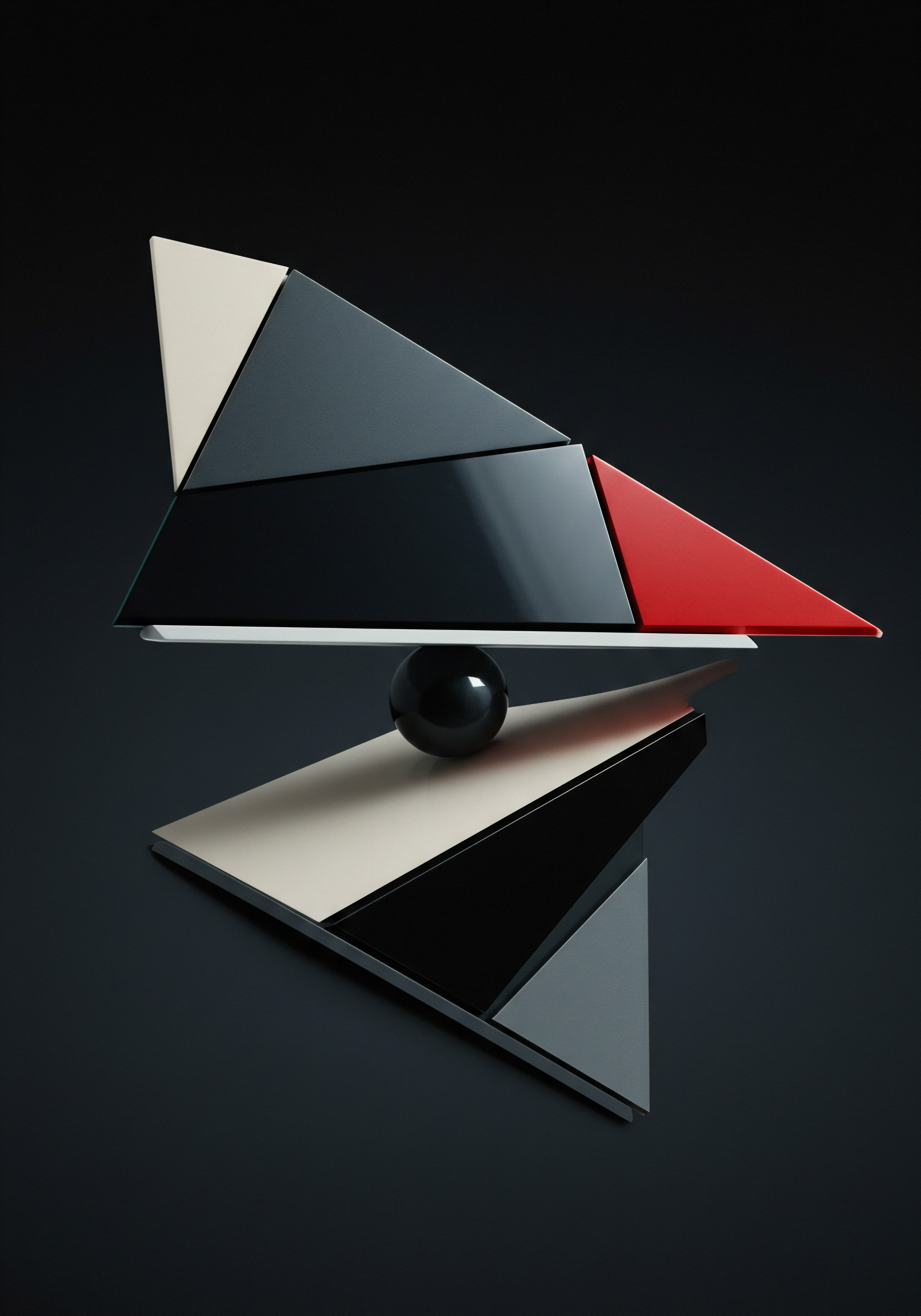

Organizational learning is not a monolithic entity. Business scholars often categorize it into different types, such as single-loop learning, double-loop learning, and deutero-learning. Single-loop learning, the most basic form, involves correcting errors within existing routines and processes. Automation excels at this level, standardizing processes and minimizing deviations.

However, double-loop learning, which entails questioning underlying assumptions and revising organizational goals, and deutero-learning, or learning how to learn, are far more complex and require a different kind of engagement. The question arises ● Does automation primarily facilitate single-loop learning at the expense of these deeper, more transformative learning types in SMBs?

The Risk of Learning Silos in Automated Systems

Automation, by its nature, often leads to specialization. Employees may become highly proficient in operating specific automated systems or managing particular automated workflows. While this specialization can enhance individual efficiency, it can also inadvertently create learning silos within the organization. Knowledge becomes concentrated within specific roles or departments directly involved with the automated systems, potentially limiting the broader dissemination of learning across the SMB.

For instance, in a small e-commerce business, the marketing team might become adept at using automated marketing platforms, while the customer service team remains largely disconnected from this learning. This siloed approach can hinder cross-functional learning and limit the organization’s ability to synthesize knowledge from different parts of the business. The challenge for SMBs is to design automation implementations that actively promote knowledge sharing Meaning ● Knowledge Sharing, within the SMB context, signifies the structured and unstructured exchange of expertise, insights, and practical skills among employees to drive business growth. and break down these potential learning silos.

Tacit Knowledge Erosion and Automation

A significant concern regarding automation’s impact on organizational learning is the potential erosion of tacit knowledge. Tacit knowledge, often described as “know-how,” is the unwritten, experiential knowledge that employees accumulate through practice and direct involvement in processes. Many SMBs thrive on the tacit knowledge of their experienced employees, which is crucial for problem-solving, innovation, and adapting to unique customer needs. When processes are automated, particularly those that previously relied heavily on manual skills and judgment, there is a risk that this tacit knowledge is not captured or transferred.

For example, a small custom furniture maker might automate aspects of its design process using CAD software. While this can speed up design creation, it might also reduce the opportunity for apprentices to learn the nuanced craft of furniture design directly from master craftsmen, potentially leading to a loss of valuable tacit knowledge over time. SMBs must consider strategies to explicitly capture and codify tacit knowledge before or during automation implementations to mitigate this risk.

The Role of Data and Feedback Loops in Automated Learning

Automation systems generate vast amounts of data, providing SMBs with unprecedented insights into their operations. This data can be a powerful tool for organizational learning, but only if SMBs can effectively interpret and utilize it. The creation of effective feedback loops Meaning ● Feedback loops are cyclical processes where business outputs become inputs, shaping future actions for SMB growth and adaptation. is crucial. Data from automated systems needs to be translated into actionable information that informs decision-making and drives continuous improvement.

However, many SMBs lack the analytical capabilities or the time to effectively process this data. They may be overwhelmed by the sheer volume of information or lack the expertise to identify meaningful patterns and trends. Therefore, simply implementing automation and generating data is not enough. SMBs need to invest in developing data literacy within their teams and establish clear processes for analyzing data, extracting insights, and feeding these insights back into their operations and strategic planning. Without these feedback loops, the learning potential of automation data Meaning ● Automation Data, in the SMB context, represents the actionable insights and information streams generated by automated business processes. remains largely untapped.

List ● Intermediate Considerations for Automation and Organizational Learning

- Learning Type Alignment ● Assess whether automation initiatives primarily support single-loop learning or if they can be designed to foster double-loop and deutero-learning.

- Knowledge Silo Mitigation ● Implement strategies to promote cross-functional knowledge sharing and prevent the creation of learning silos around automated systems.

- Tacit Knowledge Preservation ● Develop methods to capture and codify tacit knowledge before or during automation implementations to prevent its erosion.

- Data Feedback Loop Development ● Invest in data literacy and establish processes for analyzing automation data and using it to drive continuous improvement Meaning ● Ongoing, incremental improvements focused on agility and value for SMB success. and informed decision-making.

- Employee Role Evolution ● Redefine employee roles to focus on higher-value activities that complement automation, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and innovation.

Strategic Integration for Enhanced Learning

To move beyond the potential pitfalls and fully leverage automation for organizational learning, SMBs need to adopt a more strategic and integrated approach. This involves viewing automation not as a standalone solution but as a component within a broader organizational learning ecosystem. It requires a conscious effort to design automated systems and workflows in a way that actively promotes learning, knowledge sharing, and adaptation.

This might involve incorporating human-in-the-loop elements into automated processes, creating opportunities for employees to interact with and learn from automation data, and fostering a culture of experimentation and continuous improvement. The intermediate stage of understanding automation’s impact on organizational learning in SMBs is about moving beyond the initial focus on efficiency and recognizing the deeper, more nuanced ways in which automation shapes how these organizations learn, adapt, and ultimately, thrive in the long run.

Strategic integration of automation with organizational learning initiatives is crucial for SMBs to realize the full potential of technology without sacrificing their adaptive capacity.

Advanced

Within the nuanced landscape of small to medium-sized businesses, the adoption of automation technologies presents a paradox. While automation promises operational efficiencies and scalability, its impact on organizational learning is far from linear, often manifesting in complex, multi-dimensional ways that require strategic foresight and a deep understanding of organizational dynamics. For SMBs, which frequently operate with flatter hierarchies and rely heavily on the agility and tacit knowledge of their workforce, the introduction of automation can trigger systemic shifts in learning patterns, knowledge flows, and the very essence of organizational adaptability. This advanced analysis delves into the intricate relationship between automation and organizational learning in SMBs, exploring the strategic, cultural, and epistemological dimensions of this technological transformation.

The Epistemological Shift ● From Experiential to Algorithmic Knowledge

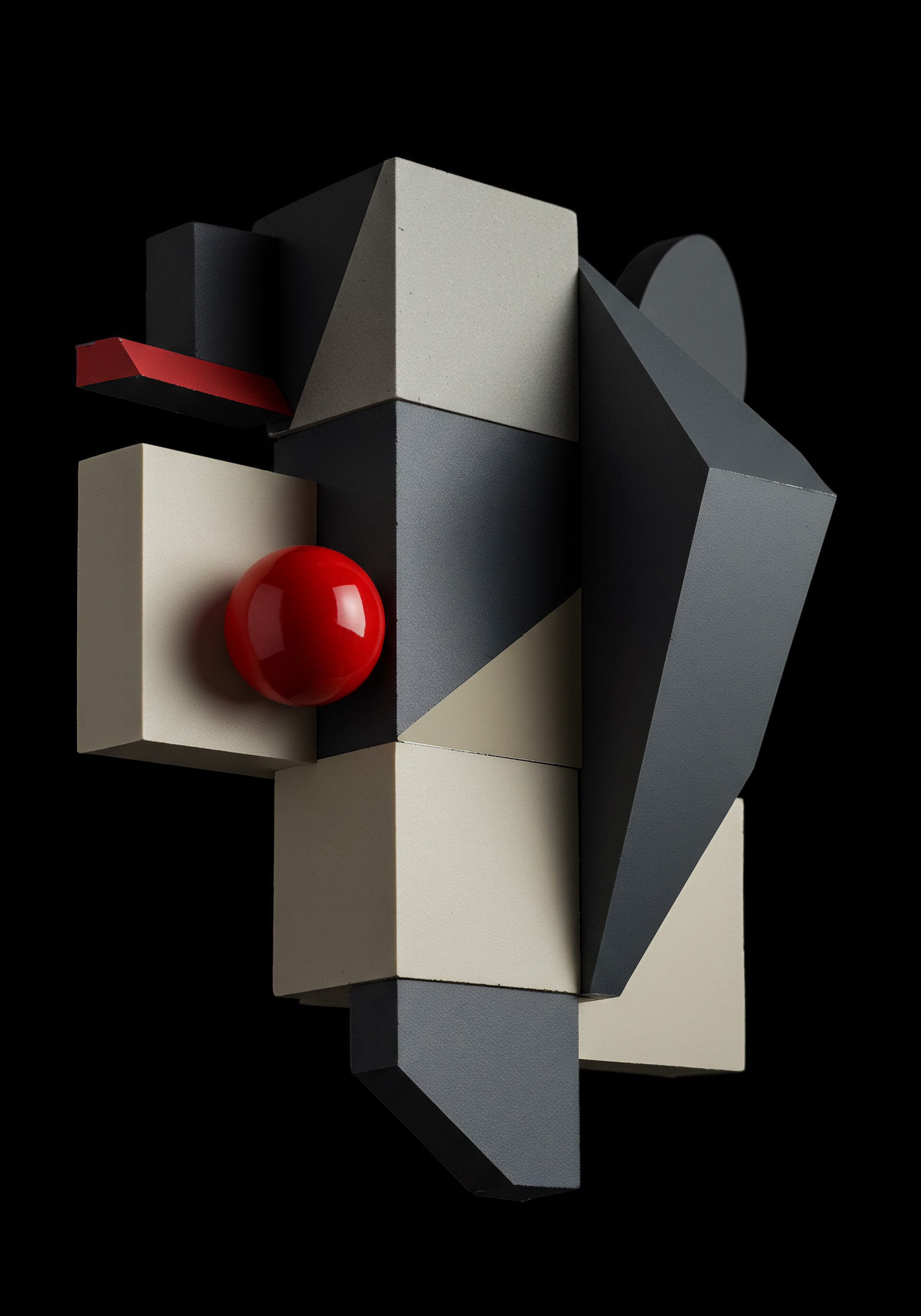

Automation fundamentally alters the epistemological basis of organizational knowledge within SMBs. Traditionally, SMBs have relied on experiential knowledge, gained through direct engagement with customers, processes, and market dynamics. This knowledge is often tacit, embedded in the skills and intuitions of experienced employees. Automation, however, introduces a shift towards algorithmic knowledge.

Decision-making becomes increasingly driven by data-driven algorithms and automated systems, which operate based on codified rules and statistical patterns. This transition can lead to a devaluation of experiential knowledge, particularly if SMBs fail to integrate human judgment and contextual understanding into their automated workflows. The challenge lies in harmonizing these two forms of knowledge ● experiential and algorithmic ● ensuring that automation enhances, rather than supplants, the rich tapestry of organizational understanding within SMBs.

Automation Bias and the Attenuation of Critical Thinking

A critical concern in the advanced analysis of automation’s impact is the phenomenon of automation bias. This cognitive bias refers to the human tendency to over-rely on automated systems, even when they provide incorrect or suboptimal recommendations. In SMBs, where resources for independent verification and oversight may be limited, automation bias Meaning ● Over-reliance on automated systems, neglecting human oversight, impacting SMB decisions. can have significant consequences for organizational learning. Employees may become less inclined to critically evaluate the outputs of automated systems, leading to a decline in critical thinking skills and a reduced capacity for independent problem-solving.

This attenuation of critical thinking can be particularly detrimental to double-loop learning and innovation, as it discourages questioning assumptions and exploring alternative perspectives. SMBs must proactively mitigate automation bias through training, process design, and the cultivation of a culture that values critical inquiry and human oversight Meaning ● Human Oversight, in the context of SMB automation and growth, constitutes the strategic integration of human judgment and intervention into automated systems and processes. of automated systems.

The Transformation of Learning Pathways and Knowledge Flows

Automation reshapes the pathways through which learning occurs and knowledge flows within SMBs. In pre-automation environments, learning often happened organically, through informal interactions, mentorship, and on-the-job experience. Automation can disrupt these informal learning pathways, particularly if it reduces human interaction and creates more structured, system-driven workflows. Knowledge flows may become more centralized, channeled through automated systems and data repositories, potentially limiting the lateral and distributed knowledge sharing that is often characteristic of agile SMBs.

To counter this, SMBs need to consciously design new learning pathways that leverage automation while preserving the benefits of informal learning and distributed knowledge. This might involve creating virtual communities of practice around automated systems, implementing knowledge management Meaning ● Strategic orchestration of SMB intellectual assets for adaptability and growth. platforms that integrate with automation data, and fostering a culture of open communication and knowledge sharing across automated and non-automated functions.

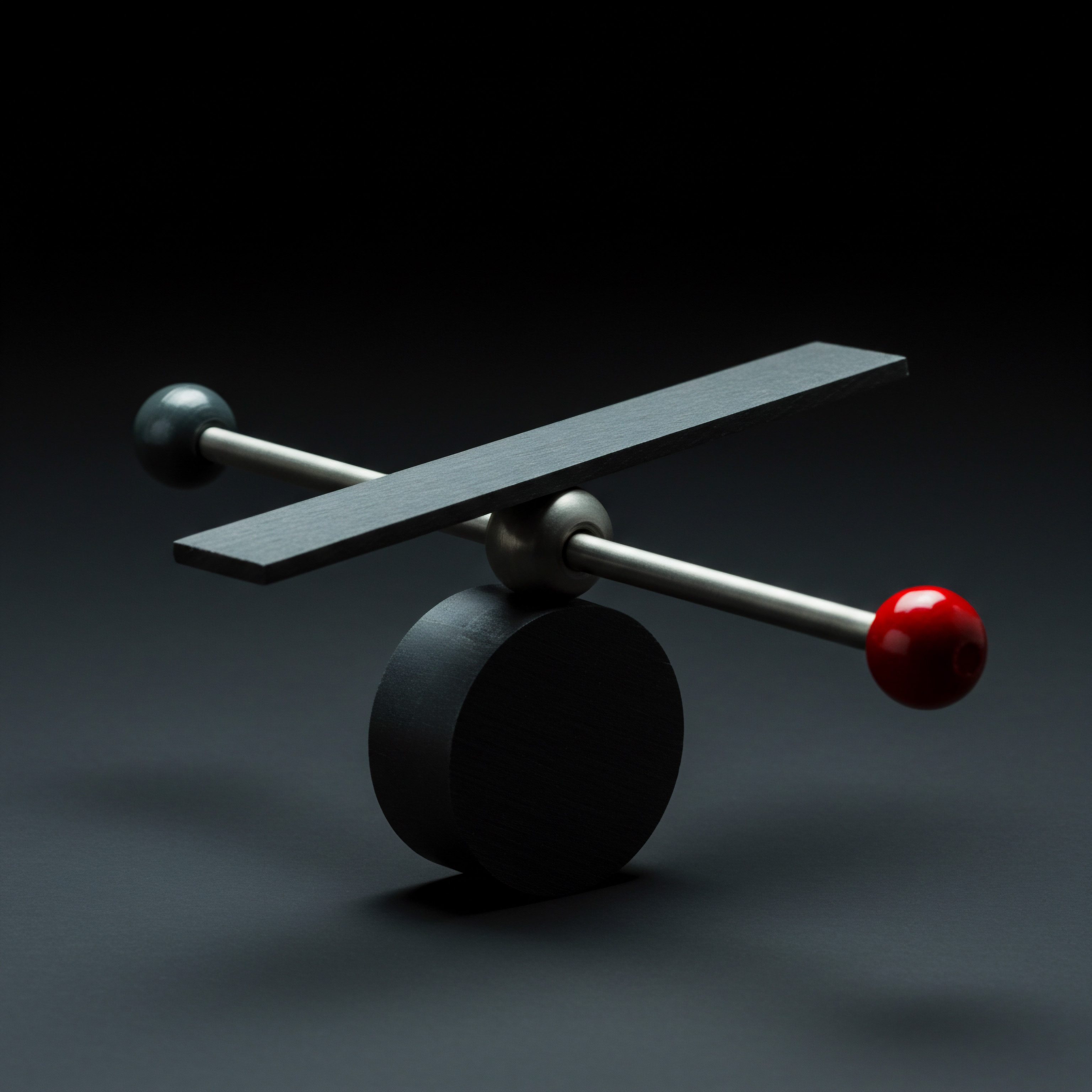

The Strategic Imperative of Human-Automation Symbiosis

At the advanced level, the optimal approach to automation in SMBs Meaning ● Automation in SMBs is strategically using tech to streamline tasks, innovate, and grow sustainably, not just for efficiency, but for long-term competitive advantage. is not about replacing humans with machines, but about fostering a symbiotic relationship between them. Human-automation symbiosis Meaning ● Human-Automation Symbiosis for SMBs: Strategic partnership of human skills and automation for enhanced efficiency and human-centric growth. recognizes the unique strengths of both humans and automated systems and seeks to leverage these strengths in a complementary manner. Automated systems excel at processing large volumes of data, performing repetitive tasks, and identifying statistical patterns. Humans, on the other hand, possess critical thinking, creativity, emotional intelligence, and the capacity for complex judgment and contextual understanding.

By strategically combining these capabilities, SMBs can create learning ecosystems that are both efficient and adaptive. This requires a shift from viewing automation as a purely technological solution to seeing it as a strategic partner in organizational learning and development. It necessitates a deliberate focus on upskilling and reskilling employees to work effectively alongside automated systems, focusing on higher-value tasks that leverage uniquely human capabilities.

Table ● Advanced Considerations for Automation and Organizational Learning in SMBs

Advanced Consideration

Description

Strategic Implication for SMBs

Epistemological Shift

Transition from experiential knowledge to algorithmic knowledge; potential devaluation of tacit knowledge.

Harmonize experiential and algorithmic knowledge; codify tacit knowledge; integrate human judgment into automated workflows.

Automation Bias

Over-reliance on automated systems; attenuation of critical thinking and independent problem-solving.

Mitigate automation bias through training, process design, and fostering a culture of critical inquiry and human oversight.

Learning Pathway Transformation

Disruption of informal learning; centralization of knowledge flows; potential limitation of distributed knowledge sharing.

Design new learning pathways that leverage automation while preserving informal learning and distributed knowledge sharing; create virtual communities of practice; implement knowledge management platforms.

Human-Automation Symbiosis

Strategic partnership between humans and automated systems; leveraging complementary strengths.

Focus on upskilling and reskilling employees; redefine roles to emphasize uniquely human capabilities; design workflows that integrate human and automated tasks synergistically.

Ethical and Societal Implications

Consideration of broader ethical and societal impacts of automation on workforce, skills gaps, and economic equity.

Engage in responsible automation practices; invest in workforce development; contribute to broader societal dialogues on the future of work.

Ethical and Societal Dimensions of Automated Learning

Beyond the immediate organizational impacts, the advanced analysis of automation and organizational learning in SMBs must also consider the broader ethical and societal dimensions. Widespread automation raises questions about workforce displacement, skills gaps, and economic equity. SMBs, as integral parts of local communities and economies, have a responsibility to engage in responsible automation practices.

This includes considering the impact of automation on their workforce, investing in upskilling and reskilling initiatives, and contributing to broader societal dialogues about the future of work Meaning ● Evolving work landscape for SMBs, driven by tech, demanding strategic adaptation for growth. in an increasingly automated world. The advanced perspective recognizes that automation is not merely a technological or economic phenomenon, but also a social and ethical one, requiring SMBs to adopt a holistic and responsible approach to its implementation and impact on organizational learning and beyond.

Advanced SMB strategy in the age of automation demands a holistic, ethical approach, fostering human-machine symbiosis and addressing broader societal implications.

References

- Argyris, Chris, and Donald Schön. Organizational Learning ● A Theory of Action Perspective. Addison-Wesley, 1978.

- Easterby-Smith, Mark, and Marjorie A. Lyles. Handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management. 2nd ed., Blackwell Publishing, 2011.

- Fiol, C. Marlene, and Marjorie A. Lyles. “Organizational Learning.” Academy of Management Review, vol. 10, no. 4, 1985, pp. 803-13.

- Levitt, Barbara, and James G. March. “Organizational Learning.” Annual Review of Sociology, vol. 14, 1988, pp. 319-40.

- Schilling, Melissa A. Strategic Management of Technological Innovation. 6th ed., McGraw-Hill Education, 2021.

Reflection

Perhaps the most unsettling aspect of automation’s integration into SMBs isn’t the displacement of jobs, but the potential displacement of thought itself. As SMBs increasingly rely on algorithms to optimize processes and inform decisions, are they inadvertently outsourcing their cognitive agility? The very struggle to adapt, the messy process of trial and error, the human debates and disagreements that fuel genuine organizational learning ● these may be subtly eroded by the seductive efficiency of automated systems.

The future SMB might be impeccably optimized, yet strangely less capable of truly original thought, trapped in a loop of algorithmic refinement rather than radical innovation. The question isn’t just about learning to use automation, but about ensuring automation doesn’t unlearn us.

Automation in SMBs intricately reshapes organizational learning, demanding strategic integration Meaning ● Strategic Integration: Aligning SMB functions for unified goals, efficiency, and sustainable growth. to balance efficiency with adaptive capacity.

Explore

What Role Does Culture Play In Automated Learning?

How Can SMBs Measure Automation Learning Effectiveness?

Why Is Human Oversight Still Vital In Automated SMB Operations?